I just cubed a mango, which is one of my personal Proustian memory triggers.

In my Senior year of high school, I took the advanced level French course (did we call it French 4 or French 5? I can’t recall). It’s a joke that I even took the course. In my school system, languages were primarily taught via memorization. Whether conjugated verbs or categorized vocabulary for various assumed frequent-use topics (weather, food, transportation), you’d be given a page or three of words to memorize as homework. The next day, you’d have written or spoken drills in class. We even memorized scripted conversations, often echoed back to a tape of “native speakers”:

Bonjour…Bonjour Jean…Bonjour Marie…Bonjour Jean et Marie…Comment va tu?…Pas mal, merci, et toi?…Pas mal, merci.

When there was extemporaneous conversation, the emphasis was on being linguistically correct over expressing your thoughts. From the earliest I can remember, I’ve learned most effectively through context. Even when I was acting, I’d learn my lines better by putting the work up on its feet than by reading the lines over and over to myself. Rote memorization has never been my friend, I lack that magical language-music-math gene, and I grew up in a monolingual environment. Put it all together and you get a miserable language student (though, should I ever run into Jean and Marie, I can successfully say hello and let them know I’m fine, thank you).

However ineffectual my attempts to learn, I continued to dream of someday speaking another language, and I knew that the teacher of the only advanced French class was Henry Solganik. He was one of the younger, cooler teachers. More than that, he was vibrant with life and the implication of a world far wider than our neighborhood in Queens.

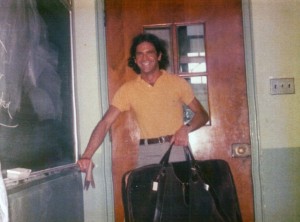

So in my final year in high school, I made one more attempt to learn some French. This time, thanks to Henry, something stuck. What happened that year was that French was finally freed from drills and scripted “conversations,” to become a living language. We read Sartre and Racine—aloud, and with tremendous overacting. As we might have done had we been raised in France, we read Le Petit Prince and Le Petit Nicholas. I also recall thumbing through issues of Paris Match. Not only did we read, but we spoke. We discussed current events and what we did over the weekend. Henry told us about some of his travels. His travels were an important part of who he was to us, fundamental enough that, when we wanted to give him a present to say “thank you,” we chose to buy him the suitcase you can see in the snapshot above.

I know there’s much else I’m forgetting about that class; but I can haltingly express myself in French if I have to, and there are two important moments I will always remember.

We were smart kids, but Henry knew how narrow our horizons were. He decided to broaden them before we launched out into the world. At the end of the year, he treated us all to dinner in Chinatown. The enormity of his generosity must be considered in light of the size of the class (there were about 30 of us; he split us into two groups to do this) and the fact that teachers’ salaries were even lower (proportionately) than they are today. The only qualification was that he would be ordering the meal, and we must each absolutely taste every single item that was put on the table. In an almost hysterical state of anticipation, we took the subway downtown and followed Henry to the restaurant. We’d all eaten a lot of what we considered to be Chinese food (Americanized Cantonese), but even those whose families might have ventured downtown had never been to a place like this. It was a half-basement space, and dimly lit, the combination making it seem far more exotic that it probably was. The maitre d’ greeted our teacher like a friend and showed us to the large round table. Food started coming out. With each new plate that arrived, Henry would scan our faces with wicked glee. Some of what he’d ordered was actually familiar, and even the more mysterious dishes weren’t scary once we tried them. Except, that is, for the snails. They came in the shell, with toothpicks to dig them out. We didn’t know what to do so, with one trembling eye remaining fixed on our own plates, we watched him demonstrate. Then he sat back and, grinning from ear to ear, watched. I remember sticking the toothpick into the shell and wiggling until I pulled out what looked like an inch and a half version of a pencil eraser. I held it gingerly between my teeth and snapped my mouth shut before I could decide not to. It was as chewy as an eraser, too; and it honestly didn’t taste like much of anything. Yes, the first snail I ever ate in my life was overcooked and under-seasoned. But this peculiar not-horrible mouthful, consumed in a strange place but among safely-familiar faces, made me feel worldly and adventurous. It was probably the first adult meal of my life, and the memory became a kind of mascot to bring me courage when confronting the unknown.

At some point during that same year, one of my classmates (I think it was Thalia Gross) brought a mango to class. During the years of my childhood, pineapples were about the most exotic produce any of us encountered. The closest we came to other tropical fruits was the label on the can of Hawaiian Punch. I don’t think there were even two of us who’d ever seen a mango. Henry’s face lit up like the sun. I’m sure that’s why she brought it to class; she knew he’d know what do. He took out his pocket knife and ran it around the edges to halve it, then scored the halves and turned them inside out. He passed the halves down the rows of desks. Each of us in turn nipped a single cube of sweet flesh from the skin and passed the rest down. Unlike the snail, the mango was a revelation to me. It was what I thought Olympian ambrosia must taste like.

During that final year of childhood, I was lucky enough to spend 40 minutes a day with a teacher who thought not only of the schoolwork we needed to master but of the wider world we would explore once we ventured past our own backyards.

I remember Henry Solganik, and that moment on the frontier, every time I cut open a mango.